In 1890, Reginald Brabazon, 12th Earl of Meath, was invited by a clergyman acquaintance to address the young men of his congregation. The boys had been lured by the promise of “a half-crown spread for a penny” and the vicar was anxious to find a speaker who might be interesting enough to hold their attention. In an age before the phenomenon of the teenager was recognised, he was having trouble connecting with his youthful audience. After tea and cakes, the Earl decided he would entertain them with tales he had himself enjoyed, of the men who had been awarded the Victoria Cross during the Indian Mutiny. His choice of subject was spot on; the boys were enthralled but it soon became clear that, not only had they never heard about the Indian Mutiny, but nor did they know anything about India.

Lord Meath was appalled. After enquiring with the local schoolmaster he discovered that most pupils’ knowledge of history did not extend beyond Henry VIII.  How, he queried, “could one expect to make patriotic citizens of boys whose knowledge of the Empire stopped four centuries and more before their own time? They knew nothing of Great Britain’s relations with India, with America, or the later swelling Imperial note which resounded through the world, to make Britain not only the greatest political fact but the greatest political fact in the farthest-flung Empire the world has ever seen.”

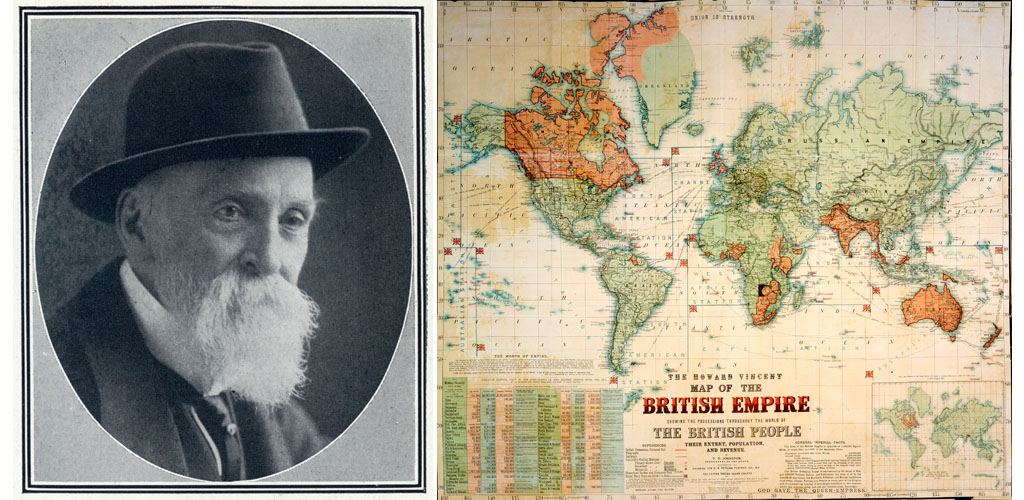

Meath, an ardent Imperialist wanted the nation’s youth to share his enthusiasm, and, after discovering the situation was similar around the country, made it his personal crusade to educate and disseminate the idea of Empire to a rising generation. Setting up an office in his home, funding his campaign with an annual budget of £5000 provided by his wealthy wife and working with two secretaries, he set to work, lobbying high profile M.Ps. By 1896, he was proposing an Empire Day, first adopted by the province of Ontario the following year.

Meath suggested May 24th, the birthday of Queen Victoria, as the most suitable day to celebrate. It would be a public holiday for all school children around Britain, “with the exception of a couple of hours in the morning, to be spent in exercises of a patriotic and agreeable nature and in listening to lectures and recitations on subjects of an Imperial nature.”

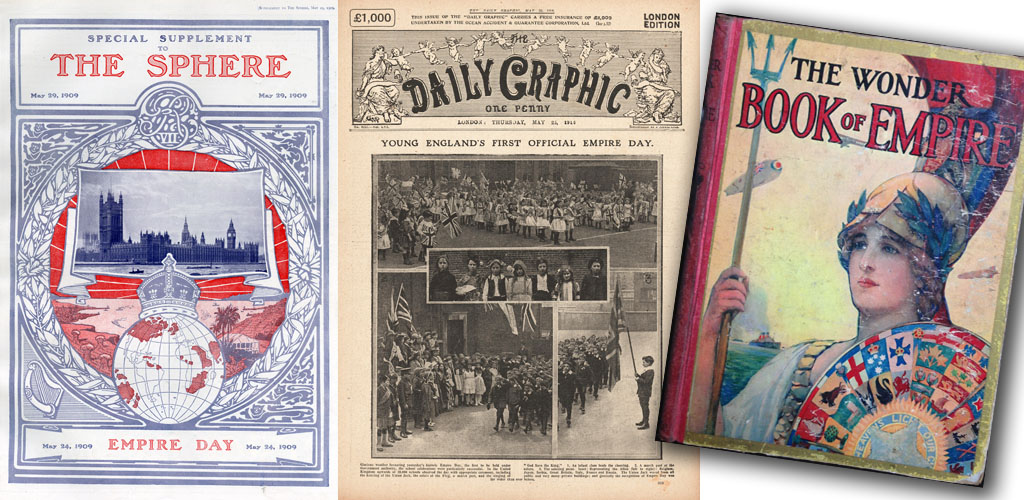

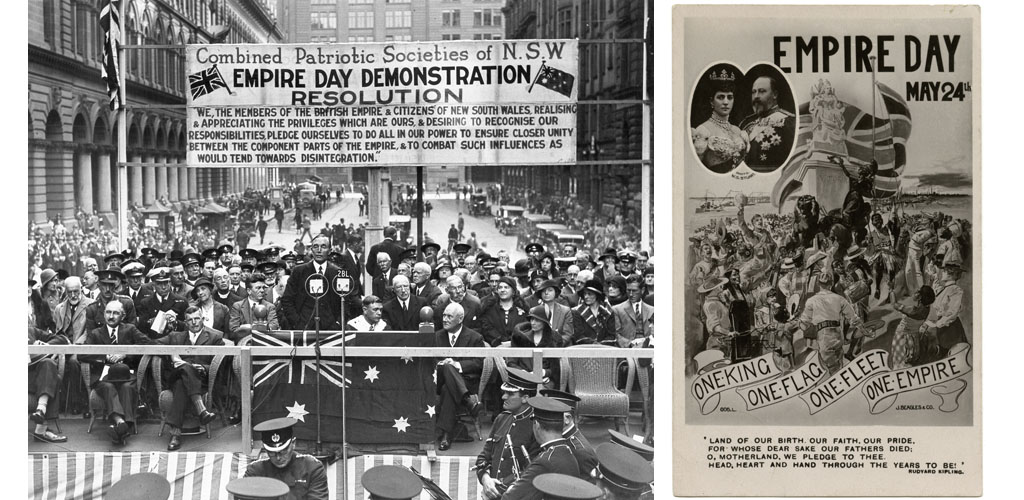

The official adoption of Empire Day around the world was gradual. In 1905, Australia recognised the May 24th celebration. In 1916, when Britain was in the tightest grip of war and a reinforcement of national patriotism was called for, King George V officially sanctioned the observance of Empire Day by ordering the Union Jack to be flown from public buildings on that day. Lord Meath however had been encouraging it far longer, though not everyone was as enthused about the idea as he was.  An opinion piece in The Bystander from 1913 had a cynical tone: “Empire Day is over and thousands of little Englanders have once more been reminded there is such an institution as the British Empire. Presumably it is with a view to blaring this fact into their ears that the excellent Lord Meath keeps the celebration so noisily going.” In 1922, the Government of India also officially adopted Empire Day though again, it had been celebrated in that country since 1907.

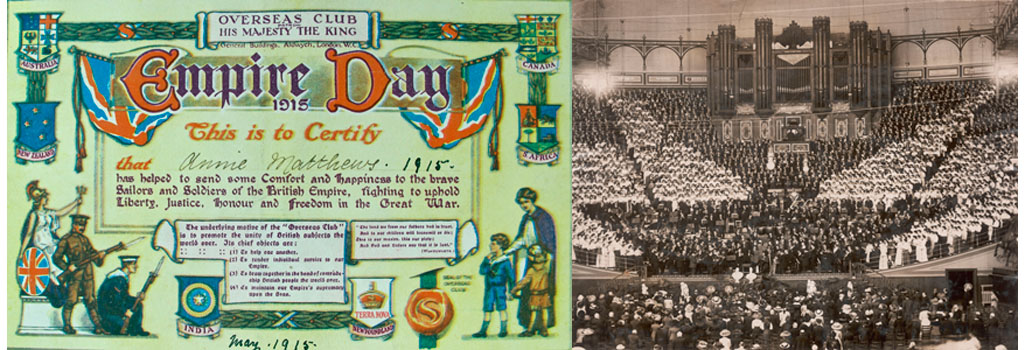

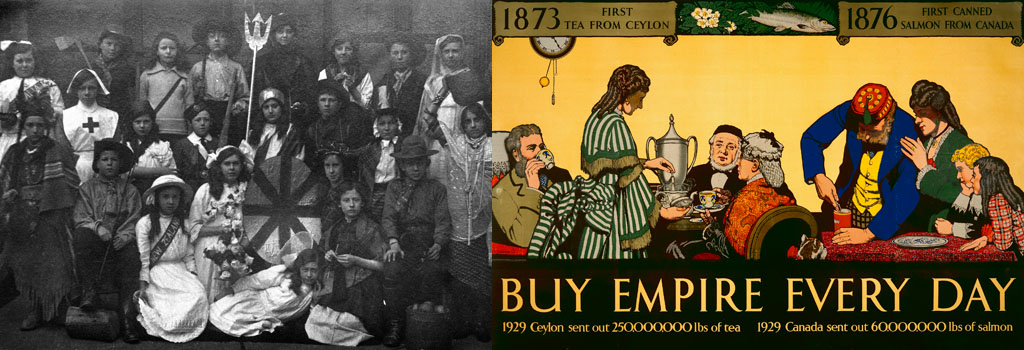

Once established in the mother country, Empire Day was a major event. In 1928, The Sphere magazine reported that 5,000,000 children took part, and in Hyde Park, 100,000 attended a celebration in Hyde Park where they were led in patriotic singing by Dame Clara Butt and the massed marching bands of the Guards played “appropriate songs”. Children in towns and villages around the country would enjoy their day off school, many dressing up in costume, sometimes to take part in a pageant of British history. Invariably, among the fancy dress costumes, there would always be at least one Britannia.

Once established in the mother country, Empire Day was a major event. In 1928, The Sphere magazine reported that 5,000,000 children took part, and in Hyde Park, 100,000 attended a celebration in Hyde Park where they were led in patriotic singing by Dame Clara Butt and the massed marching bands of the Guards played “appropriate songs”. Children in towns and villages around the country would enjoy their day off school, many dressing up in costume, sometimes to take part in a pageant of British history. Invariably, among the fancy dress costumes, there would always be at least one Britannia.

Through our eyes, looking back to over a hundred years ago, with the British Empire a dim and distant memory even for the older generation, Empire Day, with its meetings, songs and lectures sit uncomfortably with our current views and concerns over our Imperialist past and the growth of nationalism in the post-Brexit era. Subliminal brainwashing and patriotic jingoism? Or a celebration of the bonds between nations in an Empire where the sun never set? Lord Meath certainly believed it was the latter, and the movement’s motto; “Responsibility. Duty. Sympathy. Self-Sacrifice” indicated there were worthy motives behind the pomp and pageantry of Empire Day. Lord Meath died in October 1929, long before the Second World War and the final dismantling of the Empire he had done so much to promote. In its place, the Commonwealth, founded in 1949 and with King George VI, and now our present Queen as Head. With its programme of initiatives to promote peace, development and justice, the Commonwealth, currently with 53 member states, is a force for good. Commonwealth Day is held in the second week of March, and is therefore further disconnected from the Empire Day in which it is rooted. Nevertheless, pride and participation in the concept of Empire was an integral part of being British in the first half of the twentieth century and on this day a century ago, children across the world would have been looking forward to a day off school.