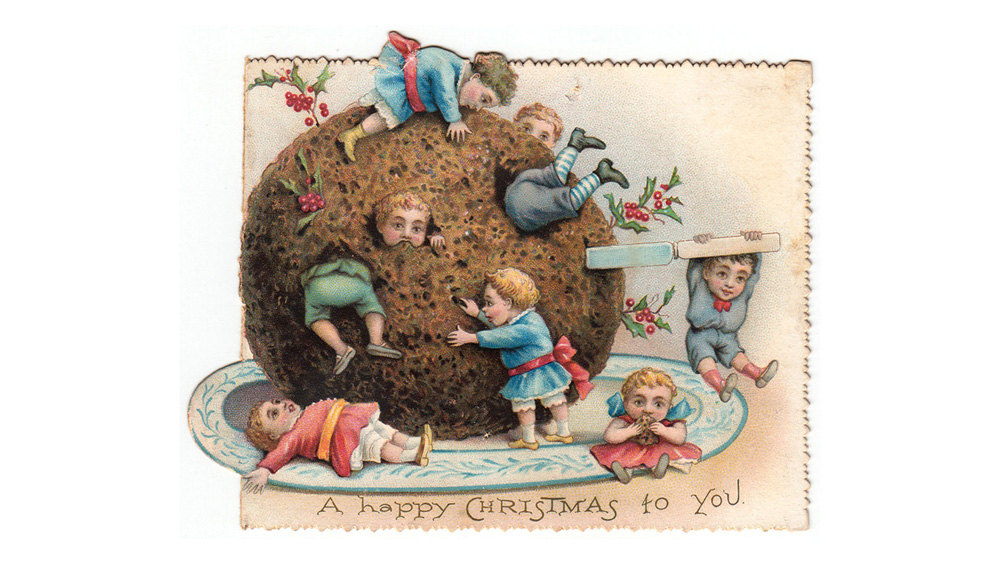

10997093: Children attacking a large pudding on a Christmas card. Date: circa 1890s

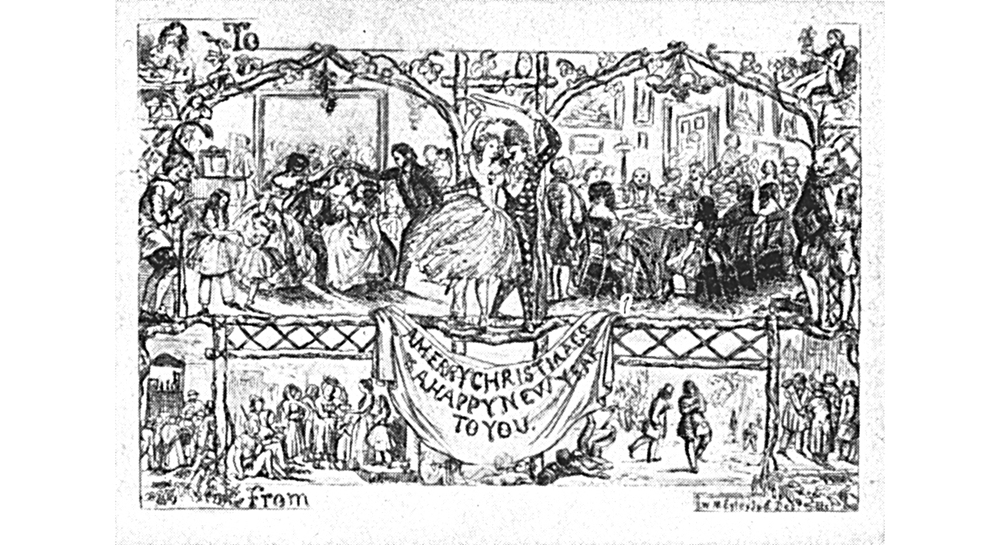

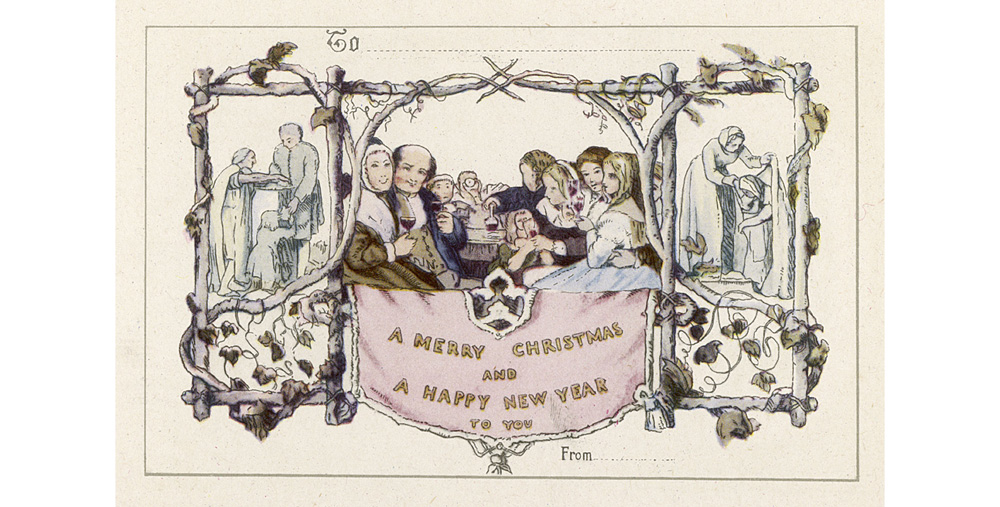

For any student of Christmas festive facts, they will know that first Christmas card was designed in 1846 by John Calcott Horsley at the request of Sir Henry Cole, later Director of the Victoria and Albert Museum. About one thousand hand-coloured copies were produced, printed by Mr. Jobbins of Holborn and published by Joseph Cundall of Old Bond Street. The design incorporated two scenes of charity flanking a central picture of a typically Victorian family cheerily raising a glass to toast the recipient of the card. Although Horsley’s card is the acknowledged ‘first’ Christmas design, another, even earlier card, was designed by Mr. W. N. Egley, and sent by the artist to friends and family in 1842. Whichever can claim to be truly the first Christmas card, they triggered a trend that became a festive tradition as familiar as trees and mince pies.

These early examples had been private ventures but by the 1860s the firm of Messrs. Goodall had begun to issue Christmas cards to the trade. In the decades that followed, Christmas card sending rose to prodigious proportions. During the Christmas period of 1882 for example, more than 14,000,000 letters and packages were delivered in the London area alone. Such was the demand for new designs of good quality that in 1879, card publishers Raphael Tuck held an exhibition at the Egyptian Hall in London, with well-known Academicians as judges and 500 guineas in prizes. The contest attracted nearly 900 entrants and was so popular that a second and grander competition, judged by Sir John Millais and Marcus Stone, was held in 1882. This time £5000 was awarded in prizes. The result was that many famous artists, including Stone, George Clausen, G. D. Leslie and W. F. Yeames, entered the Christmas card market, with one firm paying out £7000 for drawings in a single season. Years later, a 1936 interview with Desmond Tuck of Raphael Tuck published in The Sphere, revealed that each season the company rose to the challenge of creating no fewer than 3000 original Christmas card designs, achieving this with a permanent staff of fifteen designers, freelance commissions from outside artists and licensing works from art galleries and museums. Tuck were undoubtedly market leaders. They exclusively produced the royal family’s Christmas cards each year and ensured that the designs were distributed to the press who duly published them (many featured patriotic scenes or historic royals from the past), and they pioneered novelty cards alongside more sedate, traditional designs. In 1901, The Tatler magazine commented on a box of Christmas cards sent by the canny marketeers at Raphael Tuck:

“All Raphael Tuck’s cards are pretty and artistic, but what struck me as the most ingenious were the expanding cards, i.e., those cards by which a slight manipulation can be transformed into ships, soldiers and horses of a real shape and form.”

11657256: An 1842 design for a Christmas card by Mr W. N. Egley, though the general consensus is that the first was by John Calcott Horsley for Sir Henry Cole in 1846. There is some debate over whether this one was designed in 1842 or 1848. Nevertheless, a very early example, perhaps the earliest! Date: 1842

10021527: Reputedly the first Christmas card, this was designed by Horsley in 1843, and a coloured version sent out by Sir Henry Cole in 1846 Date: 1843-1846

11657260: The designing room at Raphael Tuck & Sons, fine art publishers of prints, cards, Almanacks and postcards, staffed largely by women. Tuck were one of the leading card and postcard publishers in the 19th and 20th centuries. Date: 1903

Several examples were shown but it is notable that not one single card appears to us to be particularly festive – there are donkeys on the sands of a coastal resort, a Chinese pleasure boat, circus horses and their riders, a man-o-war in full dress and eighteenth century dandies carrying a lady in a sedan chair. Not a single snowflake or twinkling bauble in sight.

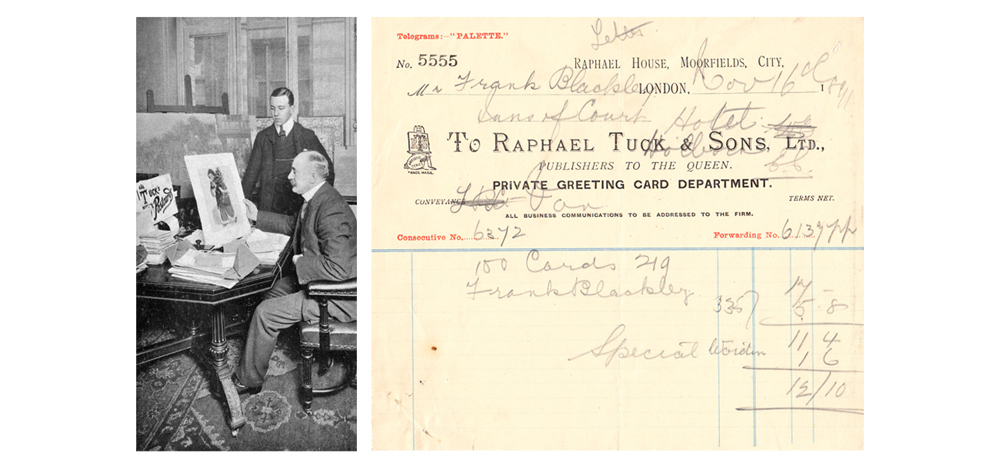

11657259 (left): Adolph Tuck, Sir Adolph Tuck, 1st Baronet (1854-1926), fine art publisher and chairman of Raphael Tuck & Sons, pictured with his son passing a design for a Christmas card in 1903

11657259 (left): Adolph Tuck, Sir Adolph Tuck, 1st Baronet (1854-1926), fine art publisher and chairman of Raphael Tuck & Sons, pictured with his son passing a design for a Christmas card in 1903

10999514 (right): Invoice from Raphael Tuck & Sons Ltd, to Mr Frank Blackley, for the supply of one hundred greetings cards, total cost ten shillings and ten pence.

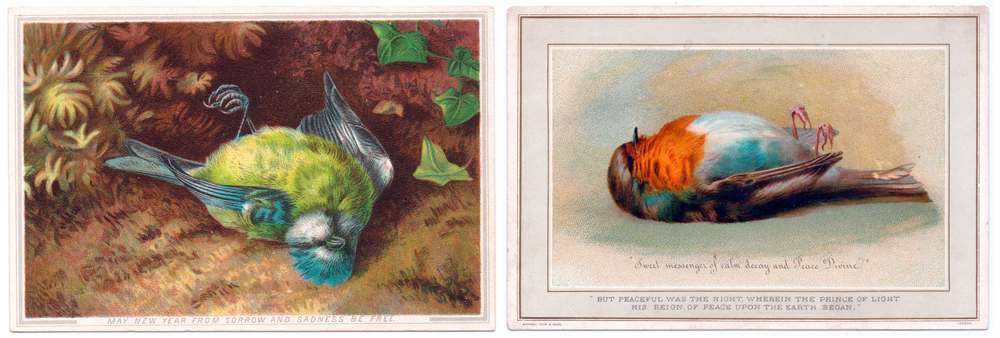

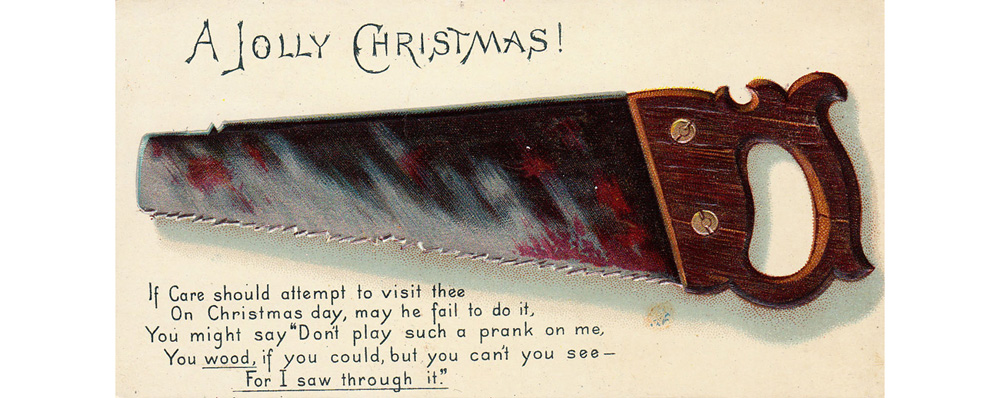

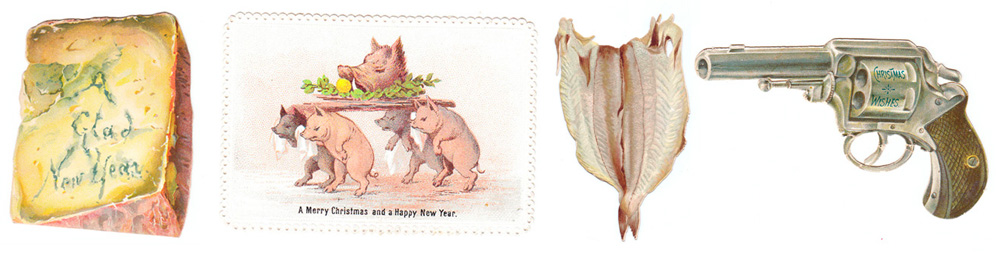

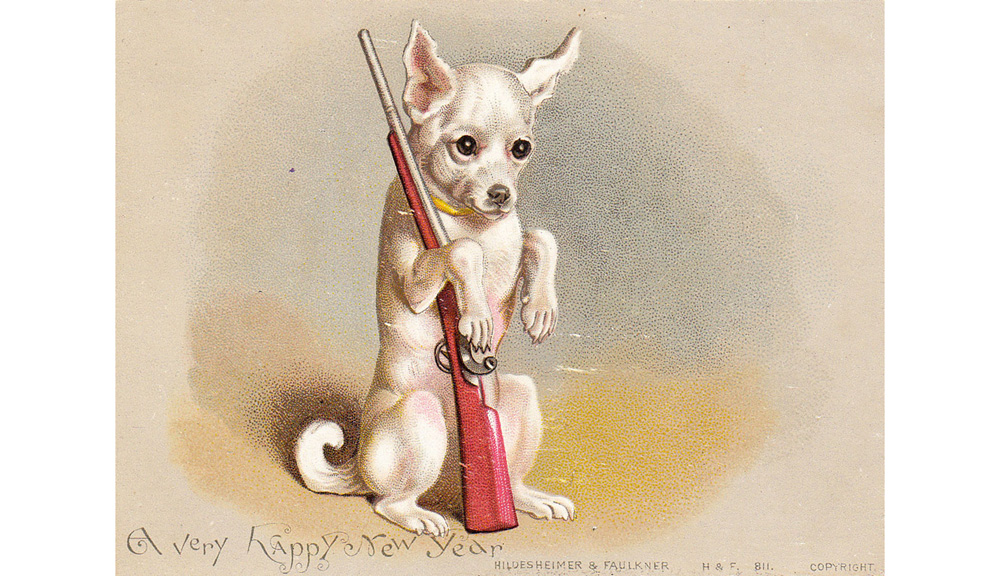

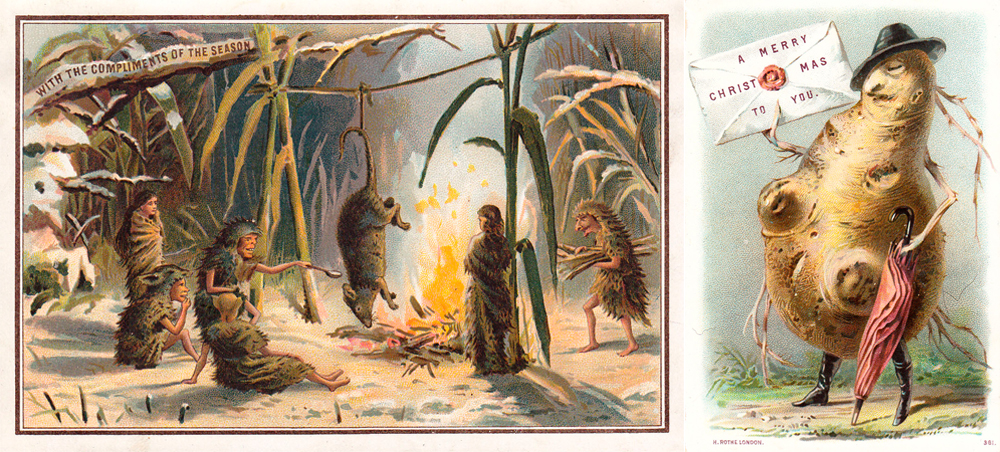

We have an eye-bogglingly varied array of historic Christmas cards in the archive representing this rich period in card publishing. Many have arrived via our representation of the fabulously bonkers David Pearson Collection featuring designs that range from the mildly inappropriate to the unashamedly weird, most from the late 19th and early 20th century. We may blame our modern-day sensibilities and taste for laughing at such unfathomable festive themes, but even in 1894, Gleeson White, editor of The Studio, wrote a monograph on Christmas cards in which he commented on the increasingly bizarre and inappropriate styles of card available to consumers.

“It is amusing to note the pictorial accompaniments, considered fit to illustrate the very mundane wish for a ‘A Happy Christmas’. To accompany this prosaic and wholly carnal greeting we find, often, monsters of nightmareland, pictures of accidents dear to the farce writer, and in short, the subjects, which are in vulgar parlance weird and alarming on the one hand and distinctly uncomfortable on the other.”

Gleeson White, aesthetically sensitive, might have been particularly averse to ‘jokey’ and strangely macabre cards but there was undoubtedly a market at a time when the scale of card-sending meant that designers had to cast about for novel ideas and not all card buyers were discerning enough to prefer the worthy work of an Academician. Nevertheless, whoever came up with murderous frogs and dead robins, cards in the shape of a hand gun or plucked turkeys lying limp and lifeless on kitchen scales, had perhaps spent rather too long at the drawing board, scraping the brandy barrel of festive ideas. We don’t care. Whether it’s Christmas or not, weird Christmas cards continue to be a source of great mirth and amusement at the library. We’re just waiting for a mischievous someone to select some for a cool and off-beat Christmas card selection box. We’ll be at the front of the queue.